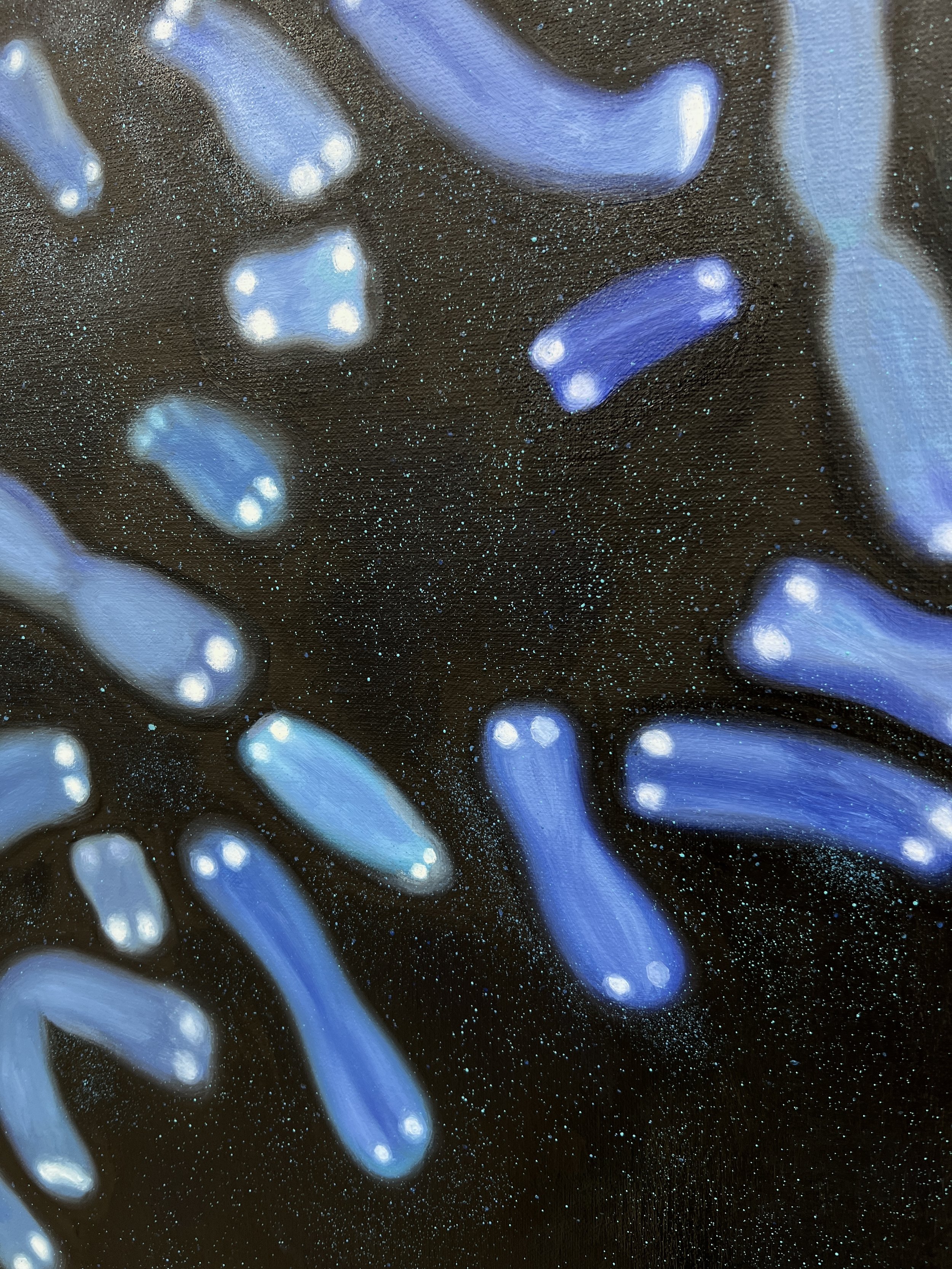

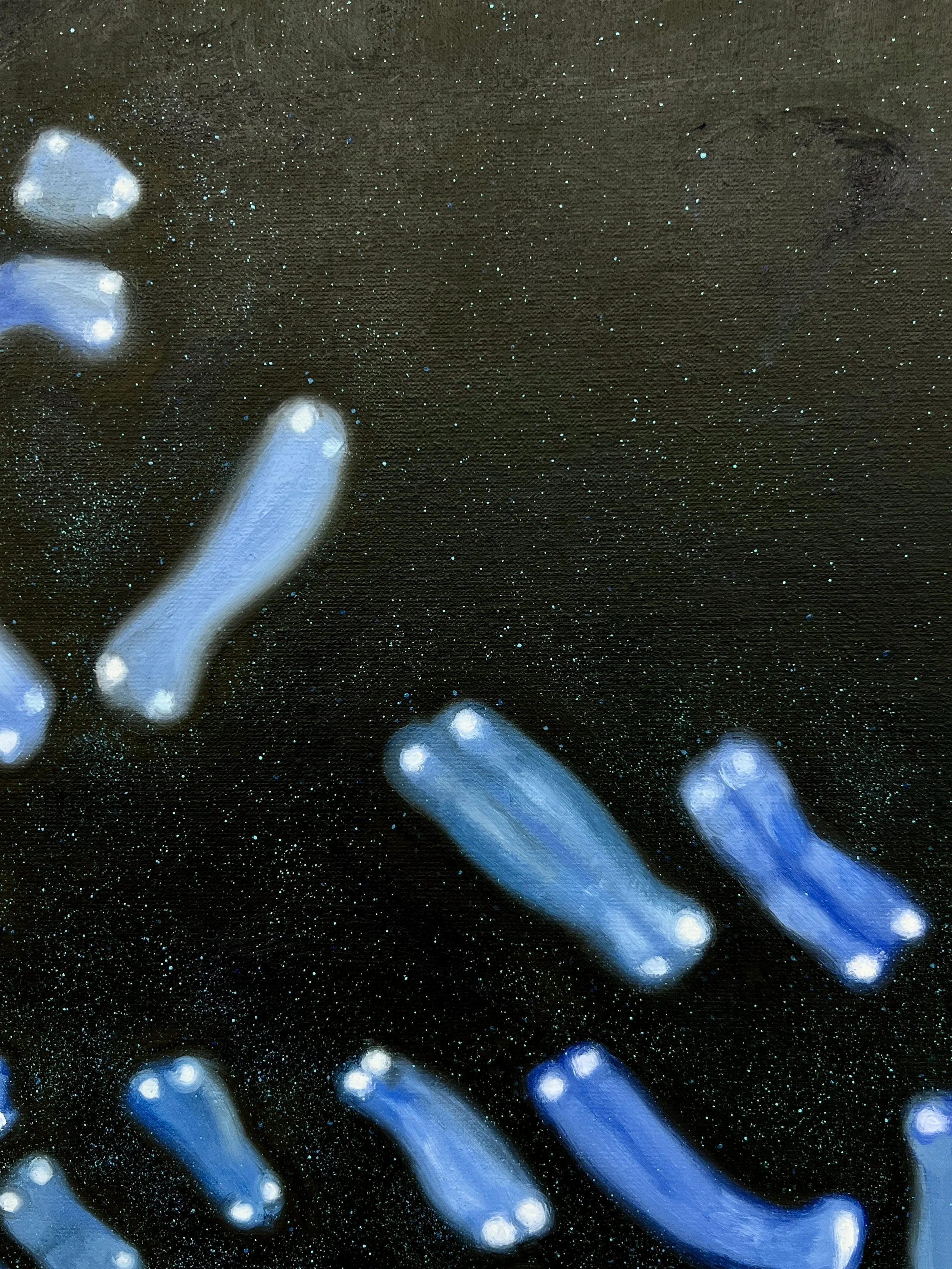

Chromosomes, 2022

Chromosomes, 2022

Oil on linen

102 x 91 cm (40 x 36 in)

Historically, sequencing the human genome as "complete" has always been a relative term. The first human genome, deciphered through the Human Genome Project (HGP) in October 1990, was a thirteen-year effort that covered most protein-coding regions but left approximately 8% of the genome unexplored. On March 31, 2022, nearly 100 scientists from the Telomere-to-Telomere (T2T) Consortium finally mapped the first objectively complete human genome.

Tan Mu examines this groundbreaking scientific milestone through the inherently interpretive and the hand-painting uncertainty of the painting medium in Chromosomes (2022). By rendering the 46 human chromosomes and their telomeres in delicate blue and white hues, the unique nature of painting contrasts with the supposed 'completeness' of the genome. This contrast emphasizes that the achievement of painting chromosomes marks the beginning of more profound research into human nature and the potential discovery of its differences from other species.

Q: How do you understand the characteristic of uncertainty in painting that you mentioned?

Tan Mu: The uncertainty I refer to is rooted in the hand painted nature of painting itself. Unlike printed laboratory images, which aim for precision and exact replication, painting always carries deviation, interpretation, and imperfection. A hand painted image can never be a one hundred percent reproduction of its source. This gap between the original image and the painted result is not a flaw, but a defining quality. It embodies individuality, time, and the physical presence of the artist.

This uncertainty allows painting to operate differently from technological reproduction. It reflects the human condition, where interpretation and error are inseparable from understanding. In this sense, painting becomes a parallel system of knowledge, one that embraces ambiguity rather than eliminating it. Each brushstroke carries decision making, hesitation, and intuition, making the image alive rather than fixed.

Q: How do you connect this uncertainty in painting to scientific progress, such as early genome decoding?

Tan Mu: This idea closely relates to my interest in early scientific visualization, particularly the initial attempts to decode DNA in the early 1990s. When I was a child, I remember seeing simplified and incomplete representations of genetic sequences in textbooks and news reports. At the time, these images were rough and speculative, limited by the technology available. Only in recent years have scientists achieved a more complete and accurate representation of the human genome, though even now there are still margins of uncertainty.

From this perspective, the uncertainty in painting mirrors the trajectory of scientific development. Early genome decoding was not perfect, yet it laid the foundation for future breakthroughs. Today, technologies such as AI driven protein modeling continue to refine this knowledge. Painting, in its imperfect and interpretive nature, echoes this process. It reflects how understanding evolves over time through approximation, correction, and refinement.

Q: How does this relate to your broader creative themes and works such as IVF?

Tan Mu: This directly connects to works like IVF, which address the decoding of genetic structures and the technologies that attempt to define life itself. Scientific advancements in chromosome mapping and protein decoding represent humanity’s desire to understand, control, and potentially transcend biological limitations. These developments carry immense promise, from disease prevention to personalized medicine.

When a major scientific milestone is reached, such as the publication of the first objectively complete human genome, I feel a strong impulse to respond artistically. One of my paintings was created just two days after such a breakthrough was announced. Seeing that news reminded me of how distant this goal once seemed during my childhood. It felt like witnessing a long arc of human curiosity finally converge.

In this sense, my work functions as a form of temporal recording. Each painting becomes a knot tied along the timeline of technological and scientific progress. I am deeply concerned with how these breakthroughs shape human destiny, and painting allows me to respond in real time, preserving the emotional and conceptual weight of these moments.

Q: What artistic techniques did you use in this painting to convey these ideas?

Tan Mu: If you look closely at the painting, the background is composed of countless small blue dots. This technique is similar to the way I depict starry skies and cosmic environments in other works. I am drawn to points as a visual language because they operate both symbolically and structurally.

In scientific imagery, these dots often represent data points or microscopic structures. In my painting, I intensified and expanded them, allowing them to resemble stars in the night sky or bioluminescent organisms in the deep ocean. This transformation connects the microscopic with the cosmic, a recurring theme in my work.

These dots also appear in the Signal series and in my explorations of noise, data, and information systems. Conceptually, they symbolize connectivity. Whether representing cells, stars, pixels, or data, they reflect my ongoing fascination with how information generates meaning across scales. Through this language, painting becomes a space where science, perception, and imagination converge.